When you call for help, they always come. We call them “everyday heroes”.

They are our first responders. Whether someone is trapped in a fire, injured in an accident on the highway, lost at sea, buried in an avalanche or the six-year-old victim of a mass shooting, they are the ones who wade into the horror and do what needs to be done.

They may not be deployed to foreign lands, and it’s not often that someone stops them on the street and thanks them for their service, yet, still, they serve. Only recently have we begun to understand the price of that service.

Every day we hear about the struggles of our returning service members and veterans and the difficulty that they have attempting to return to a “normal” life. What we have failed to recognize is the same thing playing out in the lives of firemen, police officers, EMT’s and paramedics.

“Just Part of the Job”

Would it surprise you to know that, by some estimates, first responders attempt suicide at a rate that is 10 times that of the general public? Or that few of them ever asked for help?

This past October, the United States Senate passed a resolution designating October 28th as “Honoring the Nation’s First Responders Day”. While this is certainly a worthy gesture, it is merely a small step in the right direction.

We have become aware of the potential for our combat troops to return home with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, PTSD. Since this issue has gotten so much press, it would seem that we would also be on the lookout for it with our first responders. What they are asked to do in their jobs is strikingly similar in many ways to the missions carried out by our military. In fact, a large number of first responders are military veterans. But, whether they have served in the military or not, the trauma they witness has the same effects.

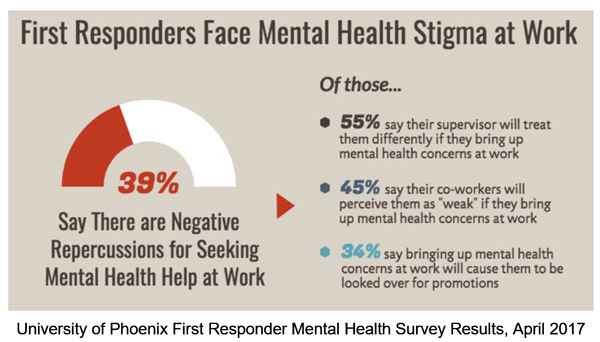

Unfortunately, most first responders have been extremely reluctant to ask for help or even acknowledge that they might be having job-related issues. Traditionally, the only accepted attitude has been that it is “just part of the job”. Anything less would risk their being singled out as someone who couldn’t be trusted. As the weak link in the team. Many have paid the price with high rates of substance abuse, destroyed families and suicide.

Connecticut state trooper, Ken Dillon, was one of the first to walk the halls of Sandy Hook Elementary School where 20 young children and 4 adults were gunned down in one of the country’s worst mass shootings. When interviewed about his own PTSD, which cost him his marriage and resulted in his arrest for DUI, Dillon said, “We rush into burning fires or deal with the worst injuries — that’s our job, it’s what we’re trained to do. But we’re also human, and sometimes our brains can’t compute the horrible things we see.”

Change and Awareness Coming Slowly for First Responders

The PTSD crisis experienced by our active duty service members and veterans has brought the issue out into the open. The simple truth is that courage and strength are no match for the toll that severe and cumulative trauma has: mental and emotional injuries are not signs of weakness.

As this awareness takes hold in the military, first responders are also finally stepping forward and seeking the help they need. The change in the culture in squad rooms and firehouses is happening slowly, but it is happening. A handful of states, Colorado, Texas, Vermont, Louisiana, Minnesota and Connecticut, have even passed legislation adding PTSD to the list of conditions that qualify for workers’ compensation for first responders. It is believed that other states will follow.

Treatment is Available for First Responders

The good news is that there is treatment available for first responders with PTSD that has proven to be highly successful. At the Brain Wellness and Biofeedback Center in Bethesda, Maryland, Dr. Mary Lee Esty and her staff are reducing or removing most, if not all, symptoms of those suffering from the effects of traumatic brain injuries and PTSD with a unique application of neurofeedback techniques. This process is totally noninvasive and passive. The client is not asked to relive the trauma, merely to sit comfortably and relax, while the neurochemical balance in the brain is being restored to its original state.

Dr. Esty devotes an entire chapter of her award-winning book, Conquering Concussion: Healing TBI Symptoms With Neurofeedback and Without Drugs, to what she refers to as the “wounds of war”. These are physical injuries to the brain as well as emotional trauma that results from being in extraordinary circumstances. According to Dr. Esty, “Everything in the book about TBI and concussion applies to first responders. During neurofeedback treatment, traumatic brain injury and PTSD resolve simultaneously.”

If you would like more information on how neurofeedback can help first responders struggling with the effects of trauma, you can find it here.